By LEE JENKINS

Published: September 14, 2004

|

|

|

The most carefully handled bat in baseball comes wrapped in cellophane.

Ichiro Suzuki curls his 5-foot-9 frame into a leather chair in the Seattle Mariners' clubhouse and peels the wrapping off his newest Mizuno bat. He stares at the shiny black barrel, as if he can see how many hits are inside. The lacquer is so thick that he can almost see his reflection.

He is at one with his bat in the way that Ozzie Smith was with his glove and Rickey Henderson was with his spikes. In a clubhouse where he has few friends and isolates himself from the international news media that follow him, Suzuki seems closest to his bat.

No one else on this last-place team has any equipment that resembles a piece of modern art. Most of the Mariners use down-home Louisville lumber, stained by pine tar and tobacco juice. Their bats are probably not much different than the one George Sisler swung back in 1920, when he banged out a major-league-record 257 hits.

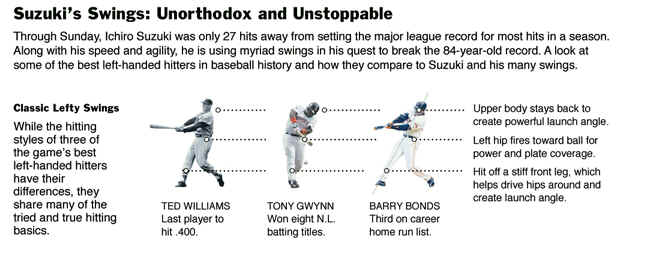

What makes Suzuki's bat unusual is not the packaging or the sheen, but the unorthodox way he uses it. He swings the bat as if it were a tennis racket, slicing balls down the line, volleying them the other way, hitting drop shots when the defense is back and hard topspin drives when they are least expected.

While hitters typically strive for one consistent swing, the 30-year-old Suzuki has developed a multitude of ways to beat a ball into the ground, flare it over a third baseman's head, sneak it up the middle or smash it into the gap.

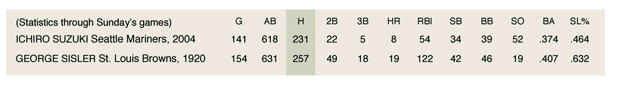

His variety of swings, unique even in his native Japan, has made him impossible to scout and difficult to defend, helping him capture the 2001 American League Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player awards and yielding a major-league-leading 231 hits this season. To eclipse Sisler's record, Suzuki needs 27 hits in the remaining 19 games. He may be the only man who could swing it.

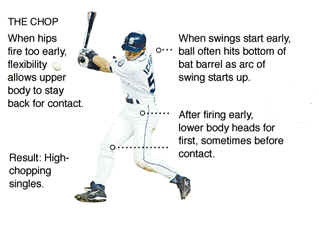

The Chop

Hitting for the Orix Blue Wave in Japan, Suzuki would wave his right leg like a pendulum with every pitch. When he reached the major leagues, he made two crucial adjustments.

Suzuki eliminated his leg motion because the pitches were faster. Then he began swinging down on the ball because Mariners Manager Lou Piniella instructed him to hit more grounders.

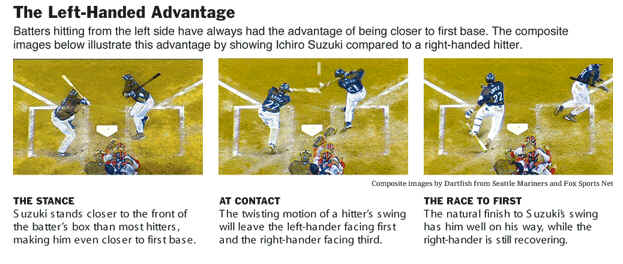

Suzuki, who bats left-handed, often heads into the batter's box intending to hit a chopper. As the pitcher winds, Suzuki starts moving toward first base. As the pitcher delivers, Suzuki focuses on the top half of the ball. When he makes contact, he is already charging out of the box.

Though Suzuki is not exceptionally fast in the outfield, he gets from home to first in a sizzling 3.7 seconds. The secret to his speed, he tells friends, "is my technique."

Most players disdain choppers because the ball is slowed by the infield grass, but for Suzuki, that is the ultimate advantage. If he hits a chopper to the left side, he forces someone to make a long throw. If he hits it to the right side, he will probably beat the pitcher to the bag. And if he hits it off the plate, which he seems to do more than anybody, no one has a chance.

On Friday against Boston, Suzuki hit one chopper off the plate and another off the mound. The Red Sox looked as if they had their pockets picked. "They joked with me about it," Suzuki said through his interpreter. "But there's nothing in the rulebook that says I can't do it."

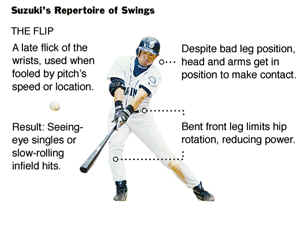

The Flip

Paul Molitor had a swing that was like a boxer's jab, short and compact, unchanging for 21 years. That swing, a portrait of consistency in a sport that prizes repetition, produced 3,319 hits and a Hall of Fame induction this summer.

It was also this summer, during his first year as the Mariners' hitting coach, that Molitor saw Suzuki swing at a 96-mile-an-hour fastball on his fists and flip it over the third baseman's head. "I don't think I've ever seen anybody handle the bat well enough to do that," Molitor said.

Suzuki has probably used more different strokes this season than Molitor did his entire career. The Flip is his most defensive swing, used when he has been fooled by a pitch and is just hoping to make contact.

He usually breaks it out for slow breaking balls, when he is out on his front foot and leaning toward first. For most hitters, such a circumstance is dire. For Suzuki, it is almost favorable.

He is perhaps most effective when his weight has shifted forward and he is relying on his wrists, his hands and his instincts. Suzuki throws the head of his bat at the ball and is somehow able to control its destination. He flicks it into the outfield, as Tony Gwynn used to do with low fastballs on the outside corner.

"The game is just different for this man," Molitor said. "He sees spaces on the field and he guides the ball where he wants it to go, like he's playing slow-pitch softball."

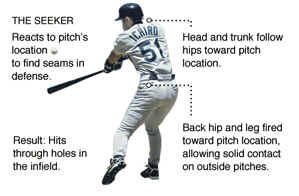

The Seeker

Players are taught from T-ball to hit every ball as hard as they can and hope it finds a hole. Suzuki treats the art of hitting as a more exact science. He changes speeds like a pitcher, slowing his swing to increase his accuracy.

As Suzuki stands in the batter's box, he looks at where the infielders are playing him and often concentrates on a target, usually up the middle or between third base and shortstop. He gauges how hard he will have to hit the ball for it to reach the hole.

If the ball ends up even a few feet away from his desired location, Suzuki will later charge into the video room between the dugout and the clubhouse. There, he sits with Carl Hamilton, the Mariners' video coordinator, and decides whether he needs to add or subtract pace. "This wasn't part of my game when I started," Suzuki said. "Along the way, I just picked it up."

His sense of timing and location has resulted in many of his bleeding singles and infield hits. Suzuki has 196 singles, breaking his American League record for singles (192 in 2001), partly because of ground balls that are placed in the perfect spot.

"He's made an art out of it," said Bret Boone, the Mariners' second baseman. "I've seen the guy have five at-bats in a game and get four infield hits. No one in baseball can get a hit in as many ways as he can. He goes up with so many different approaches, and he decides pitch to pitch which one he'll use."

The Standard

Suzuki is not hitting .371 simply with bouncers, bloopers and seeing-eye singles.

Playing in Japan, Suzuki used to retreat into an empty room before games and take hundreds of practice swings, most of them exactly the same. This is the signature swing that produces most of his singles to center field and left-center field.

He starts with his bat held high and his feet close together. When the ball is thrown, he drags his front foot slightly to start his movement. He keeps his hands back and tracks the inside of the ball so he can hit it up the middle or to the opposite field.

When Suzuki was hitting too many fly balls last year, he turned to Leon Lee, who managed him with the Blue Wave.

Lee told Suzuki that he was getting stronger with age and becoming more aggressive because he had learned major league pitching. He needed to shorten his swing and re-establish the inside-out stroke that made him successful in the first place.

Suzuki's trademark swing is not always graceful or forceful, but it allows him to foul off pitches he does not like.

He keeps his bat level through the strike zone, giving himself a better chance to hit low, sinking liners that fall in front of outfielders.

Those who follow Suzuki say that most of his other swings are variations on this approach.

"The swings look different because he's making an adjustment to every pitch," said Dave Henderson, the former major leaguer who is now a Mariners broadcaster. "But, really, he has one swing."

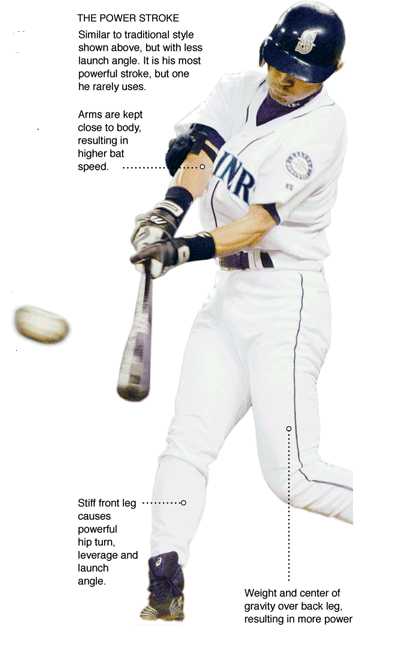

The Power Stroke

Anyone who watches the Mariners

take batting practice would assume Suzuki is the best home-run

hitter on the team. He turns on almost every pitch, blasting deep

drives to right field. His coaches remember him hitting seven

consecutive batting-practice home runs.

And, yet, Suzuki has only eight home runs. Like Wade Boggs before him, Suzuki has the ability to hit with power, but the inclination to hit for average. For Suzuki to use his power stroke, he has to feel certain he can get in front of a pitcher's fastball. Such an opportunity arises daily in batting practice, not as often in games.

"There are times when he goes up with the intention of hitting a homer," said Robert Whiting, author of "The Meaning of Ichiro." "But he does it much less here than he did in Japan."

On the rare occasion that Suzuki goes for distance, he shoots his hands out quicker than normal, tracking the ball from the outside, trying to pull it hard and high to right field. After contact, he allows himself a looping follow-through that keeps him in the batter's box longer than normal.

The power stroke probably will not help Suzuki break Sisler's record, but some of his teammates would like to see it more often. A couple of players grumbled privately last week that Suzuki bunted twice with two outs and a runner on second base.

Suzuki is caught between two spheres. While the team is desperate for run production, the organization is promoting him for the record. After every hit, the scoreboard at Safeco Field flashes his total. "At least they don't do it before I hit," Suzuki said.

In his fourth major league season, Suzuki has never been more popular or more prolific - he is almost always referred to simply as Ichiro - but he can still seem somewhat alien in his own clubhouse. The group that won 116 games in 2001 is basically gone. His close friend Mike Cameron is with the Mets.

Most everything about baseball in Seattle has changed, except for Suzuki. His singular style and creative streak are the sole reasons to watch the Mariners anymore.

No matter how many swings come and go, Suzuki remains, curled up in his chair, alone with his magical bat.