@

SURVEY: JAPAN

Oct 6th 2005

From The Economist

print edition

z

NO COUNTRY in modern history has moved so swiftly from worldwide adulation to dismissal or even contempt as did Japan, in a process that began more or less as the temple bells were tolling in the new year of 1990. In the 15 years that followed, amid crashing stock- and property markets, mountains of dud debt, scores of corruption scandals, vast government deficits and stagnant economic growth, Japan mutated from being a giver of lessons to a recipient of lectures, all of which offered recipes for its reform and revival. Those lectures, although received politely by a newly self-deprecatory Japanese elite, seemed to be ignored. Now, however, the time for lectures is over. Japan is back. It is being reformed. It is reviving.

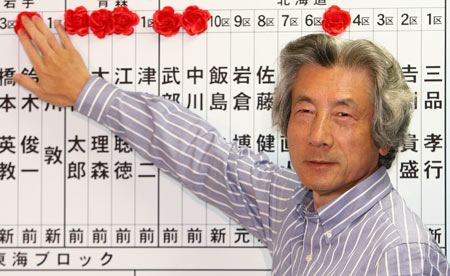

Really? The very unJapanese event that took place on September 11th?a snap general election called on a policy issue and won in spectacular fashion by the reformist prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi?has changed perceptions of Japan as an irredeemable dud, but not much. After all, the case for cynicism is compelling.

There have been several false dawns during those 15 dismal years, most notably in 1996-98 when an incipient recovery turned into a fresh recession and produced both a banking crisis and an apparent enthusiasm for reform. Since then, Japan has suffered a price deflation that has still not come to an end. Since 2001 it has had a prime minister, that same Mr Koizumi, who has talked a lot about reform but whose real achievements remain rather hard to get your arms around. Moreover, the OECD recently rated Japan's potential rate of GDP growth for the rest of this decade at a mere 1.3% a year, on the basis of poor productivity growth and a population that is shrinking and ageing. Politics didn't even come into it.

But remember. During the 1980s, when adulation (or fear) of Japan was at its peak, many observers made the mistake of assuming that because some things in the country plainly worked extremely well, everything did, so everything must be worth emulating and the trend must be ever upwards. That is why your present author named a book he published in 1989 gThe Sun Also Setsh. Japan's sun does not only rise, the book argued; trends can also bring about their own downfall. Since 1990, the opposite mistake has been made: just because some things have gone badly wrong, so everything has been assumed to be wrong, in perpetuity or at least pending a revolution. Hence the somewhat self-indulgent title of this survey: the Japanese sun does not only set, either. It also rises, and looks likely to do so from now on.

For the case for greater optimism is also strong. It is not based on any notion that Mr Koizumi's victory represents the start of radical change. Nor is it intended to suggest that privatisation of the postal savings system?the reform issue around which September's election was fought?will somehow magically turn Japan from a sloth economy to a growth one, for it won't. Rather, it is based on the view that Mr Koizumi's victory is the culmination of a long period of incremental change, bringing welcome confirmation that that change is not likely to be reversed.

Even after his landslide win, it is not inevitable that Mr Koizumi will get his way, for his party's rules stipulate that he will have merely a year as leader to exploit his new mandate. Still, there is a chance that the party will extend his term, but also a likelihood that any successor will follow the Koizumi script. This would mean that the size and role of the Japanese state will shrink, in a slow but remorseless process over the next decade or so. That will gradually help improve the public finances, which are in a mess; gradually help reduce the financial distortions that have arisen from the state's role in banking; and gradually help reform politics, which had become dependent on state cash and power.

Gradually: that could be Japan's watchword. The country has not had a revolution, nor has it gone through the gshock therapyh of reform that Margaret Thatcher deployed in Britain in the 1980s or that some central European countries tried in the 1990s, and it is not likely to go through that now. For this is not a country of revolutions, but rather one that tends to follow a course faithfully and steadily once it has been agreed upon and set.

For the past decade, although the main approach to the country's immediate macroeconomic and financial woes has been one of muddling through and hoping for the best, there has been a gradual process of reform, of setting new courses and parameters for behaviour. This has consisted of an accumulation of many small changes?some in politics, but also in financial regulation, in corporate law, in public opinion, in capital markets, in corporate mores. The two big questions have been, first, whether that process will endure; and, second, whether the burdens of the past?debt, deflation, corruption, labour protection?will continue to overwhelm the benefits that come from those changes, or whether Japan might soon be in a position to grow and develop again as a normal country might.

September's election answered the first question. But to answer that second question, it is no good speculating about politics, nor expecting the politicians to produce radical, invigorating reforms. They have neither the power nor the capability for that. The place to look is not in the fancy headlines of politics but deep in the fabric of Japan's economy and society. And although there may not be one single reason to expect a transformation, there may well be one single field of data that currently holds the clue as to whether economic recovery is going to be sustainable in the longer term, as well as exemplifying some of the biggest changes that have taken place. That field is employment and wages.

The Japan of old was known as the country of glifetime employmenth, a somewhat exaggerated but still important notion that in return for loyalty and flexibility big employers typically offered a lifetime commitment to their workers, with associated company unions, generous fringe benefits and pay rising according to age and seniority. That also made for a fairly egalitarian society. Shock therapy would have shattered the lifetime notion, producing a big rise in unemployment. So it never happened: most big companies chose to maintain their commitment, asking workers to take pay cuts and waive bonuses rather than lose their jobs, but ceased to hire new graduates. Less than half as many new graduates were hired in 2003 as in 1997.

But also, helped by changes to employment law, firms found flexibility in another way: by hiring part-timers and others on temporary contracts, both at far lower cost than for regular workers. In 1990 such gnon-regularh workers made up 18.8% of the labour force. Earlier this year, that figure reached 30%, which in Japan's 65m-strong labour force means roughly 20m people. Those workers are predominantly women, the young and the fairly low-skilled. Since 2003, the law has allowed contracts to be counted as temporary, and thus cheap, for up to three years. The use of contract workers remains forbidden in some sectors that employ lots of people, including health care and construction, but has gradually become permitted almost everywhere else. Canon, for example, a successful electronics firm that still firmly maintains a lifetime commitment for its gcoreh workers, employs fully 70% of its Japanese factory staff on such gnon-regularh terms, up from 50% five years ago and 10% a decade ago, according to Fujio Mitarai, Canon's president.

This new labour flexibility has contributed to a boom in company profits and to the paying down of debt. In 1998 workers' pay equalled about 73% of corporate earnings. By 2004 the proportion had dropped to 64%. Other factors helped too, most notably a big rise in exports to China in 2002-04, which revitalised manufacturers of all kinds, whether metal-bashers or precision engineers, and a series of bank nationalisations and mergers in 1998-2004 during which bad loans worth trillions of yen came good or were written off.

As a result, the gigantic pile of dud corporate debt for which Japan became notorious in the late 1990s is now a lot smaller: from a peak of more than ¥43 trillion in 2001, non-performing loans held by banks have more than halved to less than ¥20 trillion (see chart 2). The number is now also thought to be more or less accurate, whereas until 2001 or so official figures for non-performing loans were appallingly and deliberately underestimated.

Labour flexibility came at a price, however. Falling wages boosted profits but also weakened demand. In recent years, consumption has been sustained only by households choosing to save less of their incomes: the Japan that in the 1980s was reputed to be a nation of savers now has a household saving rate of merely 5% of disposable income, one-third of its level in 1990. New jobs have been created, but as 2005 began most were still part-time or on temporary contracts. Part-time workers in Japan get on average less than half the full-time hourly wage. The lowlier contract workers, such as shelf-stackers in convenience stores, can expect ¥600-800 per hour, which is well below the British legal minimum wage. Little wonder that an economic commentator, Takuro Morinaga, topped the bestseller charts in 2003-04 with a book on how to live on ¥3m a year. So much for the idea of Japan as a high-cost country.

As long as wages were falling and the new employment being created was the cheaper, less secure sort, there was little chance that economic growth could become truly sustainable. The cost-reduction and flexibility may have been a necessary condition of eventual recovery, but could not itself bring it about. Rather as in America during the Great Depression, declining demand has helped to neutralise improvements taking place elsewhere in the economy. Moreover, there are limits to what export-led growth, the great hope of 2002-04, can achieve, given Japan's already large current-account surplus (3.6% of GDP), the chance that the yen will strengthen against the dollar and the danger of slower demand in Japan's top foreign markets, China and America.

Since April, however, the employment data have shown something new and more promising: full-time employment is growing faster than the part-time sort for the first time in a decade, and although some of that growth is still in full-time contract work, regular employment is rising too. Wages are also rising, at their fastest rate since 1998 (which mainly means they are simply rising, at last), and bonuses are again being paid.

It is still early days?too early to tell how strong this rise in employment and incomes will prove to be. Probably, its effect will be gradual: people may try to rebuild their savings rather than spending all their gains, competition from low-cost China and India will help limit wage gains, and firms scarred by the past 15 years are unlikely to embark upon an investment and hiring binge. What this development does suggest, though, is that the last of the three excesses that have burdened the economy since 1990?excess corporate debt, excess capacity and excess labour?may now finally be on the point of elimination.

Learning to spend again

Learning to spend again

Elimination is probably too strong a word, for whether something is excessive is a subjective question. The ratio of debt to operating profits for large and medium-sized firms is down to levels typical in the 1980s, ie, less than 10%, compared with 15-20% at the peak in 1999. Smaller firms still hold debt of nearly 15% of operating profits, but that too is down from over 20% in 1999. Excess capacity is a particularly subjective matter: the capacity-utilisation rate reported by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is back up to 1992 levels, and businessmen's perceptions, as reported in the Bank of Japan's regular Tankan survey, are that excess capacity has largely disappeared.

The important issues now, though, revolve around risk, stability and incentives. During the 1990s, although Japan experienced only stagnation rather than collapse, there was always a risk that collapse might come. With corporate debt cleaned up and banks reformed, that risk has gone. Banks certainly think so: their lending has recently started to expand again for the first time since 1998. The alternative now seems to be either slow growth or faster growth, not growth or slump. Moreover, an economy that relies on increases in private spending, by households and by companies, is likely to follow a more stable path than one that depends solely on export demand or public spending. What matters most, though, is how that spending will be used. And that is a question of whether the incentives governing such spending have changed: the incentives for companies to waste the money or use it well, and the incentives for politicians and bureaucrats to abuse it, steal it or otherwise distort it.

That is where the many other small changes come in. A simple way to understand what happened to Japan in the 1980s and 1990s is that a country with many strengths, especially a high average level of education, formidable technology and powerful social co-ordination within companies, came to lose its basic disciplines and incentives, particularly in the late 1980s when it experienced one of the biggest asset booms in world history. Flushed with success and with seemingly costless capital, companies expanded and diversified recklessly. Banks lent regardless of risk or business viability. Bureaucrats and politicians resisted calls for deregulation that could have extended competition and encouraged innovation, because they did not think it was necessary. Interest groups anyway blocked change, chiefly by bribing politicians. The mass media were largely suborned by the political and corporate establishment.

The collapse of the stock- and property booms after 1990 and the ensuing recession might have been expected to shake all this up. It didn't, for two main reasons. The first was that the principal economic response to the slump, ie, massive public-works spending, further enriched some pressure groups and many politicians, making them even more able to resist change, and an expansionary monetary policy deadened the price mechanism that ought to have imposed discipline. The second was that for a mixture of social and psychological reasons, neither bureaucrats nor companies chose to admit what was really happening.

A 15-year gradual work-off of the excesses inherited from the 1980s would not have been what most analysts would have recommended or even expected in 1990, whether they were rude foreign lecturers or polite Japanese. And it has been a more painful period than any visits limited to prosperous Tokyo would suggest. Provincial cities and rural areas have suffered greatly, with shuttered-up streets and rising levels of poverty. Suicides have soared, up more than 50% since 1990 to 34,500 in 2003. By Japan's standards, crime has risen too, though it remains low in comparison with America and most of western Europe. Still, compared with what might have happened in most other developed countries had they gone through the same prolonged experience, Japanese society has remained remarkably stable.

Yet although society has been stable, the appearance of policy paralysis is misleading. Actually, bit by bit, step by step, a great deal has been changed, in what may come to look with hindsight like a sort of revolution by stealth. The changes are still continuing and being battled over, so it is too soon to judge whether that word will in the end be justified. But what this revolution-in-progress has already done is to alter many of the incentives surrounding political and corporate behaviour.

It needed to, because in 1985-95 Japanese companies proved incredibly bad at using their own money?or rather, their shareholders' money. Neither commercial law nor the courts helped the shareholders' cause very much. Banks supposedly provided the discipline in the system through their ability to intervene in their big customers' affairs when things went wrong, but such interventions became rarer as the asset bubble inflated, and then rarer still once the banks got into at least as much trouble as their customers. Then, banks kept alive what became known as gzombieh companies for fear of acknowledging their bad loans, of creating unemployment or of upsetting the whole collective applecart.

This used to be called financial socialism, which was meant as a compliment. That time has long gone. Now, a joke is circulating in Tokyo about Chinese students on a course there. Someone asks them why they spend so much time with other Chinese rather than with Japanese students. Their answer: because we are afraid the Japanese might teach us communism. The way things are going, the joke might soon become obsolete.

The sun also rises

Oct 6th 2005

From The Economist print edition

Japan's chances of prosperity and

influence look surprisingly bright

IT HAS taken an extraordinarily long time, but Japan really is

now recovering from its debt- and deflation-ridden stagnation of

the past 15 years. Proper jobs are being created, wages are

rising and economists are raising their forecasts of economic

growth?all despite worries about high oil prices and an American

slowdown. The prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi, grabbed the

world's attention last month by calling and winning a snap

general election, as a referendum on economic reform. Foreign

investors are rushing to Tokyo so as not to miss the fun. There

is a spring in the step of Japanese politicians and diplomats,

relieved that they no longer have to apologise for Japan's

weakness, pleased that they might now be better placed to deal

with those bumptious Chinese. They have to pinch themselves to be

sure it isn't all a dream.

In a way, it is. The turnaround in perceptions of Japan has been

so sudden that it risks being overdone. The immediate road ahead

for the economy still looks bumpy, with prices continuing to

fall, albeit slowly, overall lending contracting and a big budget

deficit of 6.4% of GDP making tax rises look probable. With their

wages rising and jobs feeling more secure, consumers may soon

start to spend more, allowing economic growth to be led by

domestic demand rather than by exports and capital investment.

But that process too is likely to be gradual, as households may

well also rebuild their savings, which have been depleted during

the past decade.

Gloomy old hands then turn to the longer term to prove that after

autumnal optimism will come winter. Japan's population is

starting to shrink, and so is its labour force. With productivity

growth meagre in recent years, that implies a bleak future: the

OECD recently calculated the country's potential growth rate till

2010 at a mere 1.3% a year. Mr Koizumi is a radical only by

Japanese standards, and his party rules give him but one more

year in power. And China, surely, is the real star of Asia,

destined to out-sprint the sluggish, over-rigid Japanese and

eventually to dominate the region's politics as well as its

economy.

Japanese tortoises

In the short term, it is right to be cautious. Japan's immediate

prospects matter greatly for a world worried about slowdowns

elsewhere, and forever depressed about reform and recovery in the

other great has-been economy, Germany. But, better though they

look, they could be prey to both external shocks and the vagaries

of the economic cycle. The longer term is much more important,

for both economic and political reasons. If the world's

second-biggest economy is doomed to a genteel decline, then East

Asia in future will have one great economic power rather than two

and no one to balance China's rise except India, way over to the

west, or an over-extended America, across the ocean.

Yet Japan is not doomed to decline. The slow and steady really do

win races, and not just in fables. As our survey in this issue

argues, Japan has been going through a long wave of incremental

reforms, which together have changed politics, the economy and

financial markets far more than most people realise, promising

the country a bright long-term future. September's election

result confirmed that that process is now accepted and that it

will continue, with a steady slimming of the state's role in the

economy. Until the corporate debt burden had been shed, and until

deflation has ended, those reforms always looked beside the

point, too weak to counter the ever-present risk of economic

meltdown. With that risk gone, the pile of incremental reforms

now has a chance to make a difference. And the crucial difference

they will make is to the incentives governing corporate,

political and financial behaviour.

Chinese hares

The slow growth in productivity that makes OECD forecasters

gloomy about Japan's potential was a consequence of the country's

astonishing waste of capital during the 1990s, combined with a

reluctance to cut jobs. Money was misallocated during the great

stock and property bubble of the 1980s, but then even more was

wasted in the next decade, as banks kept gzombieh companies

alive and politicians raided the biggest pork barrel in history.

Now that is past, even a modest improvement in the allocation of

capital and the use of labour would boost returns and

productivity. Reforms in corporate law and changes in the capital

markets make it likely that the improvement will be better than

modest. And, as workers become scarce again, further investment

in information technology and other sorts of automation should

boost productivity.

The ageing and shrinking of Japan's population over the next

10-15 years could thus raise productivity, not reduce it. With

labour short, sentiment and social concern will not impede

efficiency, as they did in the over-manned 1990s. And the

strengths that made Japan rich in the 1970s and 1980s?good

education, advanced technology and smooth co-ordination within

companies?will again come to the fore.

There is plenty more to be done if Japan is to achieve this

brighter, high-productivity future. Pension and health costs need

to be cut; Japan's universities need to be revamped; antitrust

policy needs to be reinforced in order to foster more

competition. Above all, the politicians need to avoid messing up

macroeconomic policy by raising taxes too sharply.

If all that is done, however, great prizes are within reach:

rising productivity, rising living standards, a rising

international reputation and, above all, a rising chance to face

up to China on equal, or even superior, terms. Japan's

relationship with China is a scratchy, tense affair; the latest

dispute concerns gas and gunboats (see article). If

conflict?diplomatic or military?is to be avoided, Japan needs to

become stronger, but also to foster other Asian alliances,

perhaps through European-style regional institutions. To its

Asian neighbours, the Chinese hare is impressive but also

worrying. A Japan that showed itself to be a steady, prosperous

and reliable tortoise would be an appealing counterweight. In

Japanese fables tortoises do win races, but they are also

something else: they are symbols of potency.