TOKYO, Nov. 7 ー When Hideki Matsui takes the field Saturday in an exhibition baseball game against an all-star team from the major leagues, he will not only play for the Yomiuri Giants, but also for a nation saying its bittersweet goodbyes.

November 8, 2002 The New York Times

Japan's Home Run King Is Leaving

By KEN BELSON

Hideki Matsui will play

baseball this weekend not only for the Tokyo Giants, but also for

a nation saying its bittersweet goodbyes.

TOKYO, Nov. 7 ー When Hideki

Matsui takes the field Saturday in an exhibition baseball game

against an all-star team from the major leagues, he will not only

play for the Yomiuri Giants, but also for a nation saying its

bittersweet goodbyes.

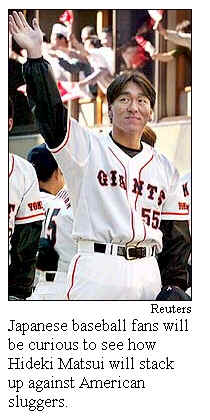

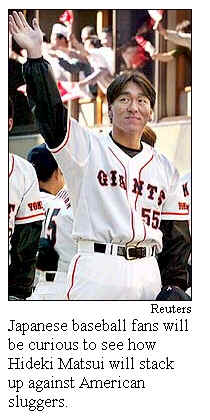

Matsui, Japan's most popular and perhaps most talented player, declared himself a free agent last week with the intention of joining a major league team. The announcement, which was not unexpected, set off a wave of conflicting emotions in this baseball-crazed country. Many Japanese were saddened by the loss of another star, while others are eager to see how the country's home run king stacks up against Barry Bonds and Sammy Sosa.

His impending exit,

though, is far more meaningful than the departure of a capable

hitter. Unlike Hideo Nomo, Ichiro Suzuki or the other Japanese

players who have left for North America in recent years, Matsui

plays on Japan's most powerful team. By ditching a career with

the Giants that guaranteed him access to wealth and power, Matsui

has put his own goals ahead of the expectations of his employer

and society at large, no mean feat in a country where conformity

is a virtue.

In doing so, Matsui has deepened the woes of Japanese baseball,

which suffers from an imbalance of power that leads to lopsided

pennant races ー the Giants

won the Central League by 11 games this year ー and frustrated fans. The Giants are the

oldest and one of the only profitable baseball franchises and so

dominate the sport that half the country's fans root for them.

With so much attention lavished on the team, which is owned by

Japan's largest media conglomerate, competition sags and

attendance wanes.

For the next week, though, as Matsui takes curtain calls at

stadiums around the country, the question millions of fans will

ask is whether he can be as successful in America as he has been

in Japan. In his 10 seasons with the Giants, Matsui, a center

fielder, has belted 332 home runs and batted .304, missed only a

handful of games and led his team to the Japan Series four times.

His dominance at the plate and rough complexion earned him the

affectionate nickname Godzilla.

But Matsui, while mild-mannered and upbeat with his adoring fans,

is also shy and understated, which may raise questions about

whether he is a fit for a city like New York. In a solemn news

conference Nov. 1, Matsui was almost apologetic about his

decision to pursue his dream of playing in the United States.

"I tried to tell myself I needed to stay here for the

prosperity of Japanese baseball," he said, pausing to catch

himself, "but in the end I decided to go with what my gut

said. I will do my best there so the fans" ー the Japanese fans ー "will be glad I went."

Such homespun honesty is typical of the 28-year-old Matsui. He is

unmarried and something of a loner on his star-studded team. With

all of Japan and much of America watching his every move, the

private Matsui will face enormous pressure to perform in public

but maintain the self-discipline he has displayed at home.

"As long as he has his own set of rules, that's what really

matters," said Suzuki, the Seattle Mariners' right fielder,

who made his own trans-Pacific journey two years ago. "The

records, numbers and opinions of other people are

secondary."

In some ways, Matsui is an unlikely candidate for the challenges

that await him in America, where fans will not be as

unquestioningly loyal and where the news media, more than

management, shape public opinion.

Like children around Japan, Matsui started playing baseball at a

young age and joined his first organized team at 11. He was a

serious but kind-hearted youth who used his size judiciously. He

defended classmates from bullies, and when fights broke out,

friends hid behind him.

"They knew they could not beat him," said Masao Matsui,

his 60-year-old father. "Once he stared at them, they felt

overwhelmed."

On the field, his ability to drive the ball was quickly noticed,

earning him a spot on the team at Seiryo High School, where he

hit .457 with 60 home runs in three seasons. Matsui went from

local star to national legend at the high school championships in

the summer of 1992. The opposing manager ordered his pitcher to

walk Matsui five straight times. The manager was vilified and

Matsui's status was sealed.

Later that year, the

Giants ー the only team

seemingly worthy of the country's biggest high school star ー

made him the No. 1 pick in the

draft. The man who drew the winning spot in the draft lottery was

Shigeo Nagashima, the Giants' manager and former third baseman

who is Japan's most beloved player. When Matsui arrived at spring

training in 1993, he wore uniform No. 55, a nod to the

single-season home run record set by the Giants great Sadaharu

Oh.

After a slow start during his first three seasons, Matsui has not

hit fewer than 34 home runs each year. His solid performance has

won him this year's Most Valuable Player award; the league's most

lucrative contract, valued at nearly $5 million; and many

endorsements. His father even opened a museum in honor of his son

next door to the family's house in Ishikawa Prefecture on the Sea

of Japan. The museum, called the Baseball Palace, draws as many

as 18,000 visitors a month.

Even though the Giants' players are under scrutiny all year,

Matsui's name is rarely linked to the scandals his teammates

sometimes fall into. He lives in an exclusive Tokyo apartment

tower and keeps to himself. In many ways, the Japanese news media

treat him differently, protecting his straight-arrow persona and

exalted standing as the Giants' cleanup batter.

"He's the Cal Ripken of Japan, but with more punch,"

said Marty Kuehnert, a sports broadcaster and longtime resident

in Japan. "He's got the same friendliness, politeness and

diligence, and he rarely misses a game."

Many of Matsui's critics say his career has received a boost from

playing so many games in the Tokyo Dome, an indoor stadium

modeled on the Metrodome in Minneapolis. With no wind, a strong

air-conditioning system and a right-field fence only 328 feet

away, many of Matsui's home runs would have been flyouts in North

American parks, his detractors say.

Kuehnert and others dismiss such talk and say Matsui has enough

power and hand-eye coordination to succeed against faster

pitching in the bigger North American parks. At 6 feet 2 inches

and 210 pounds, Matsui is big and strong enough, too.

"As talented as he is, I don't think he is going to have a

lot of major adjustments," said Barry Bonds, who is part of

the major league team visiting Japan. "As long as he allows

himself not to be distracted and he plays as he does in his home

country, he'll do fine."

Judging by the frenzy surrounding Ichiro's arrival in Seattle two

years ago, the Japanese news media may be more distracting than

any 95-mile-an-hour fastball. Japanese journalists assigned to

cover Matsui will be under intense pressure to report even the

smallest detail of his life in the United States.

That might seem to be an invasion of privacy to American

athletes. But in Japan, where even the biggest cities are filled

with tiny, intimate neighborhoods, fans will expect nothing less

than to peer into their favorite player's living room.

This curiosity may run to extremes in Matsui's case because his

fans, having tolerated his departure from the Japanese game, will

demand success from him abroad. For a nation that has long viewed

the major leagues with awe and respect, Japanese will want Matsui

to confirm that their favorite son can compete, and succeed, on

the highest level.

As a correspondent named Gucchi wrote on a Matsui fan club Web

site: "The ceiling of Tokyo Dome is too low for Matsui. He

needs a major league field."