The New York Times August 22, 2003

A Star, Modesty Included By TYLER KEPNER

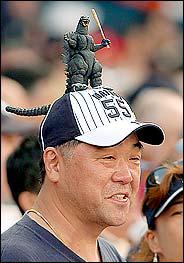

Reuters Hideki Matsui shows a humble confidence facing the news media (Japanese, in this case).

Before Hideki Matsui joined the Yankees, the person in the organization who saw him the most was John Cox, the team's coordinator of Pacific Rim scouting. Cox noticed Matsui's power, of course; that was impossible to miss. But home run potential depends on so many variables. Cox looked deeper and saw a complete player.

When the Yankees decided to pursue Matsui as a free agent, luring him from the Yomiuri Giants in Tokyo with a $21 million contract over three years, Cox told his superiors what to expect.

"In my opinion, if he can hit 15 to 20 homers and drive in 80 to 100 runs, I'd be thrilled to death, considering all the ways the game is different over here," Cox remembered saying. "All the tools he has over there can relate to the game over here."

The ability to hit for power has

been just one of Matsui's tools, and not his most impressive. The

pre-eminent home run hitter in Japan, Matsui has just 15 home

runs to go with his .294 average and 90 runs batted in, fewer

homers than such ordinary players as Tony Clark and Wes Helms.

Where Matsui stars is in all-around excellence: in the field, on

the bases, with his approach at the plate.

For all of the Yankees' recent misevaluations on player acquisitions - José Contreras, Jeff Weaver, Drew Henson, Raul Mondesi, Bubba Trammell, Armando Benitez - Matsui stands apart. He has fit in seamlessly and contributed in more ways than Manager Joe Torre could have known.

"I was talking about it with the coaching staff the other day," Torre said in Baltimore on Aug. 15 after Matsui crashed into the left-field wall for a game-saving catch against the Orioles. "When he came over here, you didn't know what kind of player he was going to be. If he was anything less than what he is, we aren't near where we are. He's given us such a lift."

Torre also said that night that Matsui's catch was the kind of play that can launch a team on a winning streak. The Yankees have not lost since.

Despite their current seven-game winning streak, it has been a tumultuous season for the Yankees, who have tried to make over the team to satisfy the championship craving of their principal owner, George Steinbrenner. Club officials have been privately agitated, and Steinbrenner has done most of his ranting behind the scenes.

Matsui has dealt with more scrutiny than any other member of the organization, and he has been unflappable. Torre calls him grounded. Matsui maintains a friendly relationship with Japanese and American reporters, understanding his demands as a celebrity but taking his stardom humbly.

"I actually don't like to act like a star," Matsui said through his interpreter, Roger Kahlon. "I try to live a normal life as much as possible and not let the stardom get to me, especially within the team. I just go out there and play."

There is no flash to the 6-foot-2, 210-pound Matsui, who is single and lives in Manhattan. Ichiro Suzuki of the Seattle Mariners is terse with the news media and cultivates an image of mystery. When Tsuyoshi Shinjo, the Mets' minor leaguer, first came to the majors, he wore bright orange wristbands and dressed as if primping on a fashion runway.

Matsui is the opposite; his patience with the news media makes him a virtual lock to win the writers' Good Guy award, and he does little to draw attention to himself.

Darrell May, a Kansas City Royals pitcher and a teammate of Matsui's in Japan, said Matsui came well-prepared for the spotlight. In the Yomiuri Giants' world, as in the Yankees', a season without a title is a failure.

"The Tokyo Giants are expected to win the championship at least once every other year, and he's the guy they looked to, to carry the team," May said. "This is relaxing compared to what he had over there. That I'm sure of."

Playing for the Giants, Matsui said, helped him deal with the expectations of playing for the Yankees. He passed Steinbrenner's first test in May, brushing off criticisms about his lack of power by essentially saying that Steinbrenner was right.

Torre was unsurprised. "That's the culture," he said. "I have trouble kidding with him, because to him, I'm the manager, and whatever I say goes. I just went up to him after those remarks and told him I'm happy with his effort, because I base it on effort. I don't necessarily base it on bottom line."

But Matsui's bottom line has improved drastically. On June 4, he was batting .250 with 3 homers. Since then, in nearly the same number of at-bats, he has a .336 average and 12 homers.

Like Derek Jeter, Matsui has shown a mastery of the fundamentals and rarely makes a mental mistake. Matsui started playing organized baseball in fifth grade, absorbing the game's nuances and sharpening his instincts through repetition.

"In Japan, they really emphasize the fundamentals," he said. "They repeat that and practice that all the time. There might be more fundamentally sound players and more balanced players over here, because you practice all the aspects."

In the outfield, those skills help Matsui overcome his lack of speed and arm strength. Watching Matsui in Japan, Cox classified his arm as "fringe, at best." But he also noticed that Matsui got the ball back to the infield as soon as he retrieved it, and figured that strong-armed infielders like Jeter and Alfonso Soriano would help him.

Cox told this to Jeter, but Jeter said he had to see Matsui for himself. He quickly realized that Cox's report was accurate.

"I can't think of anyone who gets rid of the ball as quick," Jeter said. "You see the same thing with infielders. Mike Bordick doesn't have the strongest arm at shortstop, but he gets rid of it probably quicker than anybody else. That's what Matsui does. He has the ball for a fraction of a second and he gets rid of it."

Center fielder Bernie Williams, whose own lack of arm strength has shown up more and more this season, said Matsui's other defensive skills stood out.

"He throws to the right base, he gives a hard effort all the time, and he has center-field speed," Williams said. "For a guy as massive as he is, he's got pretty good speed and he's able to get to balls. And he has soft enough hands that he can make the catch."

Matsui is 29 years old, almost 6 years younger than Williams, and he may eventually take over in center. That was Matsui's position in Japan, which makes his acumen in left field more impressive to people like the Yankees' outfield coach, Lee Mazzilli. "He hasn't played left field in nine years," Mazzilli said. "That's the remarkable thing about this."

The transition has not been flawless; Matsui has made eight errors. He said the biggest adjustment to left field was picking up the spin on the ball, which tends to tail toward the foul line. It does not feel natural to him, Matsui said, but even when he plays center, he does not want to feel comfortable. There is always something to learn.

Base running, though, has been easy. Matsui is not a stolen-base threat - he has one steal - but he rarely makes a mistake. Asked whether any part of his transition has been easier than he expected, that is what Matsui mentioned.

"I think it's probably base running," he said. "That's the only area that I really didn't have to change at all. Knowing where the ball goes, when to run, when not to run, that's been the same. I didn't have to make any adjustments. It's been an adjustment in the transition from center field to left field, and in terms of hitting against the pitchers here."

Early in the season, Matsui struggled with the two-seam fastball, a pitch that runs away from a left-handed hitter when thrown by a right-hander. Cox thought Matsui was standing too far off the plate - an idea Steinbrenner shared - but Matsui said he had simply needed to see enough of the pitch to learn how to hit it without rolling it over for a ground ball to second.

Matsui still hits ground balls, leading the American League in ground-ball outs (178) and tying for the lead in ground-ball double plays (20) through Wednesday. But a steady approach at the plate, the way he can wear down pitchers, has helped him get more pitches to drive.

"He doesn't try to do too much with the ball," Orioles catcher Brook Fordyce said. "He tries to hit it where it's pitched, like a hitter should do. You can't just take it for granted that you can throw a pitch in the strike zone. You've got to make a pretty good pitch on him, because if it's away, he'll go away, and if it's in, he'll go in, as opposed to some guy who might just swing for the home run all the time."

In a game against the Orioles in July, Matsui took a 12-pitch at-bat against Rick Helling, fouling off 6 two-strike pitches before grounding out to second. His next time up, Matsui drove a run-scoring single up the middle.

Helling, who has since been released, said Matsui reminded him of Jason Giambi. "Giambi has a pretty good approach," he said. "He doesn't swing at too many bad pitches. A lot of times he'll foul off the good ones, and if you make a mistake, it's a home run."

The biggest difference between Matsui and Giambi is in their swings; Giambi has a slight uppercut, and Matsui's swing is level, leading to more line drives. Japanese ballparks are generally much smaller, and Matsui's liners traveled over the fence more often. In his last nine seasons in Japan, he averaged 36 homers and 26 doubles a season. This year, he has 36 doubles to go with the 15 homers.

Cox thinks the home run total will rise. "Once he gets to the point where he's more comfortable with the two-seamer and the style of pitching compared to what he's seen, he's going to be fine, and the home runs will come," Cox said. "I'm still predicting that. Not necessarily next year, but I can't wait until next year to see the kinds of adjustments he makes."

Predicting his home run total has been a popular practice among Japanese reporters. But the more important number to Matsui is the one built through repetition, one by one, year by year: his consecutive-games streak. Matsui played in his final 1,250 games in Japan, and has played in all 125 Yankee games.

"It's just something that's related to my pride, being able to play every single game," Matsui said. "It's something I'm proud of, and I'd like to just continue that one, like I was in Japan. In Japan, I wanted to play in every game for the fans. Here, there aren't as many fans, and it might not matter as much. But for my own sake, and my profession, I want to play in every game."

Torre kept Matsui out of the lineup once, in April, but by the sixth inning he was in the game. Matsui wants to play every day, and Torre has obliged. In this season of changing faces and roiled tempers, there is much to be said for steady.