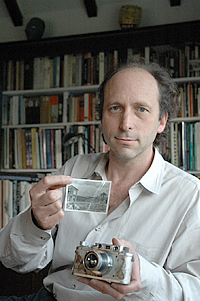

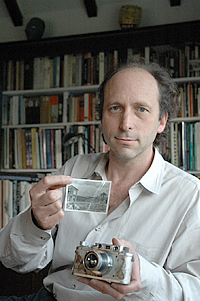

his father's camera and a photograph

he took in Nagasaki.

| The New York

Times 2005/6/20 60 Years Later, the Story

as Lived in Nagasaki |

A Nagasaki Report

By George Weller

American George Weller was the first foreign reporter to enter Nagasaki following the U.S. atomic attack on the city on Aug. 9, 1945. Weller wrote a series of stories about what he saw in the city, but censors at the Occupation's General Headquarters refused to allow the material to be printed. Weller's stories, written in September 1945, can be found below.

|

@ |  |

| American@reporter George Weller | @ | Weller's son, Anthony, holding his father's camera and a photograph he took in Nagasaki. |

NAGASAKI, Sept.8 -- The atomic bomb may be classified as a weapon capable of being used indiscriminately, but its use in Nagasaki was selective and proper and as merciful as such a gigantic force could be expected to be.

The following conclusions were made by the writer - as the first visitor to inspect the ruins - after an exhaustive, though still incomplete study of this wasteland of war.

Nagasaki is an island roughly resembling Manhattan in size and shape, running in north and south direction with ocean inlets on both sides, what would be the New Jersey and Manhattan sides of the Hudson river are lined with huge-war plants owned by the Mitsubishi and Kawanami families.

The Kawanami shipbuilding plants, employing about 20,000 workmen, lie on both sides of the harbor mouth on what corresponds to battery park and Ellis island. That is about five miles from the epicenter of the explosion.

B-29 raids before the Atomic bomb failed to damage them and they are still hardly scarred.

Proceeding up the Nagasaki harbor, which is lined with docks on both sides like the Hudson, one perceives the shores narrowing toward a bottleneck. The beautiful green hills are nearer at hand, standing beyond the long rows of industrial plants, which are all Mitsubishi on both sides of the river.

On the left, or Jersey side, two miles beyond the Kawanami yards are Mitsubishi's shipbuilding and electrical engine plants employing 20,000 and 8,000 respectively. The shipbuilding plant damaged by a raid before the atomic bomb, but not badly. The electrical plant is undamaged. It is three miles from the epicenter of the atomic bomb and repairable.

It is about two miles from the scene of the bomb's 1,500 feet high explosion where the harbor has narrowed to 250 foot wide Urakame River that the atomic bomb's force begins to be discernible.

This area is north of downtown Nagasaki, whose buildings suffered some freakish destruction, but are generally still sound.

The railroad station, destroyed except for the platforms is already operating. Normally it is sort of a gate to the destroyed part of the Urakame valley. In parallel north and south lines? here the Urakame river, Mitsubishi plants on both sides, the railroad line and the main road from town. For two miles stretches a line of congested steel and some concrete factories with the residential district "across the tracks. The atomic bomb landed between and totally destroyed both with half (illegible) living persons in them. The known dead-number 20,000 police tell me they estimate about 4,000 remain to be found.

The reason the deaths were so high -- the wounded being about twice as many according to Japanese official figures -- was twofold:

1. Mitsubishi air raid shelters were totally inadequate and the civilian shelters remote and limited.

2. That the Japanese air warning system was a total failure.

I inspected half a dozen crude short tunnels in the rock wall valley which the Mitsubishi Co., considered shelters. I also picked my way through the tangled iron girders and curling roofs of the main factories to see concrete shelters four inches thick but totally inadequate in number. Only a grey concrete building topped by a siren, where the clerical staff had worked had reasonable cellar shelters, but nothing resembling the previous had been made.

A general alert had been sounded at seven in the morning, four hours before two B-29's appeared, but it was ignored by the workmen and most of the population. The police insist that the air raid warning was sounded two minutes before the bomb fell, but most people say they heard none.

As one whittles away at embroidery and checks the stories, the impression grows that the atomic bomb is a tremendous, but not a peculiar weapon. The Japanese have heard the legend from American radio that the ground preserves deadly irradiation. But hours of walking amid the ruins where the odor of decaying flesh is still strong produces in this writer nausea, but no sign or burns or debilitation.

Nobody here in Nagasaki has yet been able to show that the bomb is different than any other, except in a broader extent flash and a more powerful knock-out.

All around the Mitsubishi plant are ruins which one would gladly have spared. The writer spent nearly an hour in 15 deserted buildings in the Nagasaki Medical Institute hospital which (illegible).

Nothing but rats live in the debris choked halls. On the opposite side of the valley and the Urakame river is a three story concrete American mission college called Chin Jei, nearly totally destroyed.

Japanese authorities point out that the home area flattened by American bombs was traditionally the place of Catholic and Christian Japanese.

But sparing these and sparing the allied prison camp, which the Japanese placed next to an armor plate factory would have meant sparing Mitsubishi's ship parts plant with 1,016 employees who were mostly Allied. It would have spared a Mounting factory connecting with 1,750 employees. It would have spared three steel foundries on both sides of the Urakame, using ordinarily 3,400 but that day 2,500. And besides sparing many sub-contracting plants now flattened it would have meant leaving untouched the Mitsubishi torpedo and ammunition plant employing 7,500 and which was nearest where the bomb up.

All these latter plants today are hammered flat. But no saboteur creeping among the war plants of death could have placed the atomic bomb by hand more scrupulously given Japan's inertia about common defense.

NAGASAKI, Saturday, Sept.8 (odn) -- In swaybacked or

flattened skeletons of the Mitsubishi arms plants is revealed

what the atomic bomb can do to steel and stone, but what the

riven atom can do against human flesh and bone lies hidden in two

hospitals of downtown Nagasaki. Look at the pushed-in facade of

the American consulate, three miles from the blast's center, or

the face of the Catholic cathedral, one mile in the other

direction, torn down like gingerbread, and you can tell that the

liberated atom spares nothing in the way. The human beings whom

it has happened to spare sit on (illegible) One tiny family board

their platforms in Nagasaki's two largest (illegible) hospitals,

their shoulders, arms and faces are strapped in bandages.

Showing them to you, as the first American outsider to reach

Nagasaki since the surrender, your propaganda-conscious official

guide looks meaningfully in your face and wants to knew:

"What do you think?"

What this question means is: do you intend saying that America

did something inhuman in loosing this weapon against Japan? That

is what we want you to write.

Several children, some burned and others unburned but with

patches of hair falling out, are sitting with their mothers.

Yesterday Japanese photographers took many pictures with them.

About one in five is heavily bandaged, but none of showing signs

of pain.

Some adults are in pain as they lie on mats. They moan softly.

One woman caring for her husband, shows eyes dim with tears. It

is a piteous scene and your official guide studies your face

covertly to see if you are moved.

Visiting many litters, talking lengthily with two general

physicians and one X-ray specialist, gains you a large amount of

information and opinion on the victims. Statistics are variable

and few records are kept. But it is ascertained that this chief

municipal hospital had about 750 atomic patients until this week

and lost by death approximately 360.

About 70 percent of the deaths have been from plain burns. The

Japanese say that anyone caught outdoors in a mile by half-mile

area was burned to death. But this is known to be untrue because

most of the allied prisoners burned in the plant escaped and only

about one-fourth were burned. Yet it is undoubtedly true that

many at 11:02 o'clock on this morning of Aug. 9 were caught in

debris by casual fires which kindled and caught during the next

half hour.

But most of the patients who were gravely burned have now passed

away and those on hand are rapidly curing. Those not curing are

people whose unhappy lot provides the mystery aura around the

atomic bomb's effects. They are victims of what Lt. Jakob Vink,

Dutch medical officer and now allied commandant of prison camp 14

at the mouth of Nagasaki harbor calls "disease." Vink

himself was in the allied prison kitchen abutting the Mitsubishi

armor plate department when the ceiling fell in but he escaped

this mysterious "disease X" which some allied prisoners

and many Japanese civilians got.

Vink points out a woman on a yellow mat in hospital, who

according to hospital doctors Hikodero (sic) Koga and Uraaji

(sic) Hayashida have just been brought in. She fled the atomic

area but returned to live. She was well for three weeks expect a

small burn on the heel. Now she lies moaning with a blackish

mouth stiff as though with lockjaw and unable to utter clear

words.

Her exposed legs and arms are speckled with tiny red spots in

patches.

Near her lies a 15-year-old fattish girl who has the same blotchy

red pinpoints and nose clotted with blood. A little farther on is

a window lying down with four children, from one to about 8,

around her. The two smallest children have lost some hair. Though

none of these people has either a barn or a broken limb, they are

presumed victims of the atomic bomb.

Dr. Uraji Hayashida shakes his head somberly and says that he

believes there must be something to the American radio report

about the ground around the Mitsubishi plant being poisoned. But

his next statement knocks out the props from under this theory

because it develops that the widow's family has been absent from

the wrecked area ever since the blast yet shows symptoms common

with those who returned.

According to Japanese doctors, patients with these late

developing symptoms are dying now a month after the bombs fall,

at the rate of about 10 daily. The three doctors calmly stated

that the disease has them nonplussed and that they are giving no

treatment whatever but rest. Radio rumors from America received

the same consideration with the symptoms under their noses. They

are licked for cure and do not seem very worried about it.

NAGASAKI, Sept.8 (cdn) --

More pieces to the broken mosaic of history are supplied by

prisoners in the liberated, but still unrelieved camps on Kyushu,

Japan's southernmost island.

While waiting for Gen. Walter Krueger's army to arrive, the

inmates are receiving humble bows and salutes from the Japanese

officers who formerly ruled them with an iron red.

By exchanging visits with prisoners from other parts of Kyushu

they are able to find out what happened in the blacked out

periods of the past.

Camp No. 14 which was inside Mitsubishi war factory area until

the atomic bomb fell there is now moved inside the eastern mouth

of the Nagasaki harbor. Here you can meet Fireman Edward Matthews

of Everett, Washington and the American destroyer Pope.

He fills in the unknown story of how the Pope fought trying to

take the cruiser Houston through the Sunda straits in the face of

a Japanese task force of "eight cruisers and endless

destroyers.

"We contacted the Japs at seven in the morning. They opened

fire at 8:30 a.m. We held out until 2 p.m., when a Jap spotter

plane dropped a bomb near out stern and watched us go down. A Jap

destroyer saw us sink. It was a perfectly clear day. They let us

stay in the water - 154 men with one 24 man whaleboat and one

life raft - for three days. We were about crazy when they picked

us up and took us to Macassar."

From Camp No. 3 at Tabata near Mojie in northern Kyushu come

three ex-prisoners who have found the lure of the open roads

irresistible after three years confinement and have come to

Nagasaki in order to view the results of the atomic bomb. Charles

Gellings of North East, Md., says, "The Houston was caught

on the eastern side or Java side of Sunda. It was in the straits

near Bantan Bay. Three hundred and forty-eight were saved, but

they were all scattered."

Chicago born Miles Mahnke, Plane, Ill., who looks all right,

though his original 215 pounds dropped to 160, says, "I was,

in the death march at Bataan. Guess you know what that was."

Here is Albert Rupp of the submarine Grenadier, who lives at 920

Belmont av., Philadelphia, "We were chasing two Nip cargo

boats 450 miles off Penang. A spotter plane dropped a bomb on us

hitting the maneuvering room. We lay on the bottom, but the next

time came up we were bombed again. We finally had to scuttle the

sub. Thirty-nine men of forty-two were saved."

Also from the submarine is William Cunningham, 4225 Webster av.

Bronx N.Y., who started with Rupp on his tour of southern Japan.

Another party of four vagabond prisoners from camps whose

Japanese commanders and guards have simply disappeared, are

Albert Johnson, Geneva, Ohio; Hershel Langston, Van Buren, Kans.,

Morris Kellogg, Mule Shoe, Tex., all crew members of the oil

tanker Connecticut, now touring Japan with a carefree marine from

North China Guard at Peking, Walter Allan, Waxahachie, Tex.

The three members from the oil tanker would like a word with the

Captain of the German raider who took them prisoner. The captain

told them that "in the last war you Americans confined

Germans in Japan; this war we Germans are going to take you

Americans to Japan and see how you like a taste of the same

medicine."

Kyushu has about 10,000 prisoners, or about one-third the total

is all Japan, mixed in the completely disordered fashion, the

Japanese used and without any records.

At Camp No.2, by the entrance to Nagasaki Bay are 68 survivors of

the British Cruiser Exeter which sank in the Java Sea battle

while trying to expel the Japanese task force. Eight inch shells

penetrated her waterline.

Five of the supposed total of nine survivors from the British

destroyer the Stronghold, sunk near the Sunda straits at the same

time are also here.

There are also 14 Britons of an approximate 100 from the

destroyer Encounter lost at the same time, besides 62 R.A.F.

mostly from Java and Singapore.

Among 324 Dutch cruisers the Java and De Ruyter were sunk at 2300

the night of Feb. 27, 1942 by torpedo attacks which the Japs

boasted were staged not by destroyers or submarines, but

cruisers.

There is also a Dutch officer from the Destroyer Koortenaer,

torpedoed by night in the Java Sea battle.

Husky Cpl. Raymond Woest, Fredericksburg, Tex., told how

remembers of the 131st Field Artillery poured 75 caliber shells

into the Japs for six hours outside Soerabaya before Java fell,

killing an estimated 700.

To correspondents eager questions about this outfit which had

been into action in Java, Wuest said that 450 members (illegible)

and were now scattered in the Far East. (illegible) Nagasaki,

whereof most were moved to Camp No. 9 (at least one further

sentence follows, but it is illegible.)

NAGASAKI, Sept.9 (cdn) --

The atomic bomb's peculiar "disease," uncured because

it is untreated and untreated because it is not diagnosed, is

still snatching away lives here.

Men, woman and children with no outward marks of injury are dying

daily in hospitals, some after having walked around three or four

weeks thinking they have escaped.

The doctors here have every modern medicament, but candidly

confessed in talking to the writer - the first Allied observer to

Nagasaki since the surrender - that the answer to the malady is

beyond them. Their patients, though their skin is whole, are all

passing away under their eyes.

Kyushu's leading X-ray specialist, who arrived today from the

island's chief city Fukuoka, elderly Dr. Yosisada Nakashima, told

the writer that he is convinced that these people are simply

suffering from the atomic bomb's beta Gamma, or the neutron ray

is taking effect.

"All the symptoms are similar," said the Japanese

doctor. "You have a reduction in white corpuscles,

constriction in the throat, vomiting, diarrhea and small

hemorrhages just below the skin. All of these things happen when

an overdose of Roentgen rays is given. Bombed children's hair

falls out. That is natural because these rays are used often to

make hair fall artificially and sometimes takes several days

before the hair becomes loose."

Nakashima differed with general physicians who have asked the

regiment to close off a bombed area claiming that returned

refugees are infected from the ground by lethal rays.

"I believe that any after effect out there is negligible. I

mean to make tests soon with an electrometer," said the

specialist.

A suggestion by Dutch doctor Lt. Jakob Vink, taken prisoner and

now commander of the allied prison camp here, that the drug

(illegible) which increased white corpuscles be tried brought the

answer from Nakashima that it would be "useless, because the

grave (illegible).

At emergency hospital No. 2, commanding officer young Lt. Col.

Yoshitaka Sasaki, with three rows of campaign ribbons on his

breast, stated that 200 patients died of 343 admitted and that

the expects about 50 more deaths.

Most severe ordinary burns resulted in the patients (sic) deaths

within a week after the bomb fell. But this hospital began taking

patients only from one to two weeks afterward. It is therefore

almost exclusively "disease" cases and the deaths are

mostly therefrom.

Nakashima divides the deaths outside simple burns and fractures

into two classes on the basis of symptoms observed in the post

mortem autopsies.

The first class accounts for roughly 60 percent of the deaths,

the second for 40 percent.

Among exterior symptoms in the first class are, falling hair from

the head, armpits and public zones, spotty local skin hemorrhages

looking like measles all over the body, lip sores, diarrhea but

without blood discharge, swelling in the throat (illegible) of

the epiglottis and retropharynx and a descent in number of red

and white corpuscles.

Red corpuscles fall from a normal 5,000,000 to one-half, or

one-third while the white's almost disappear, dropping from 7,000

or 8,000 to 300 to 500.

Fever rises to 104 and stays there without fluctuating.

Interior symptoms of the first class revealed in the postmortems

seems to show the intestines choked with blood which Nakashima

thinks occurs a few hours before death.

The stomach is also blood choked, also mesenterium. Blood spots

appear in the bone narrow and bus-arachnoydeal, oval blood

(illegible) on the brain which, however, is not affected. Going

up part of the intestines have a little blood, but the congestion

is mainly in (illegible) down passages.

Nakashima considers that it is possible that the atomic bomb's

rare rays may cause deaths in the first class, as with delayed

X-ray burns. But second class has him totally baffled. These

patients begin with slight burns which make normal progress for

two weeks. They differ from simple burns, however, in that the

patient has a high fever. Unfevered patients with as much as

one-third of the skin area burned have been known to recover. But

where fever is present after two weeks, healing of burns suddenly

halts and they get worse. They come to resemble septic ulcers.

Yet patients are not in great pain, which distinguishes them from

any X-ray burns victims.

Up to five days from the torn to the worse, they die.

Their bloodstream has not thinned as in first class and their

organs after death are found in a normal condition of health. But

they are dead - dead of atomic bomb - and nobody knows why.

Twenty-five Americans are due to arrive Sept. 11 to study the

Nagasaki bombsite. Japanese hope that they will bring a solution

for Disease X.